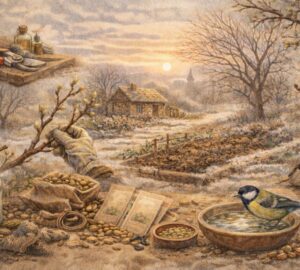

January 20 sits at a quiet but critical point in the winter calendar. Across cultures, this day was not feared for its cold — it was respected for its steadiness. Old gardeners, farmers, and observers of nature believed that what mattered now was not how harsh winter felt, but whether it could remain stable.

From European folk sayings to East Asian seasonal systems and Indigenous plant knowledge, January 20 consistently appears as a day about endurance, roots, and the value of letting winter finish its work.

Europe: Fabian and Sebastian and the Value of Steady Cold

In much of Europe, January 20 is associated with Saint Fabian and Saint Sebastian. Folk wisdom surrounding this day rarely focused on celebration. Instead, it carried a warning and a reassurance at once.

Cold on this day was considered beneficial. A firm, lasting freeze was believed to protect the land, while repeated thawing and refreezing was seen as harmful. Gardeners knew that soil covered by frost and snow remained safer than ground repeatedly exposed and softened.

Sayings linked to this date often emphasize endurance rather than change. If winter holds steady now, the garden below ground remains protected.

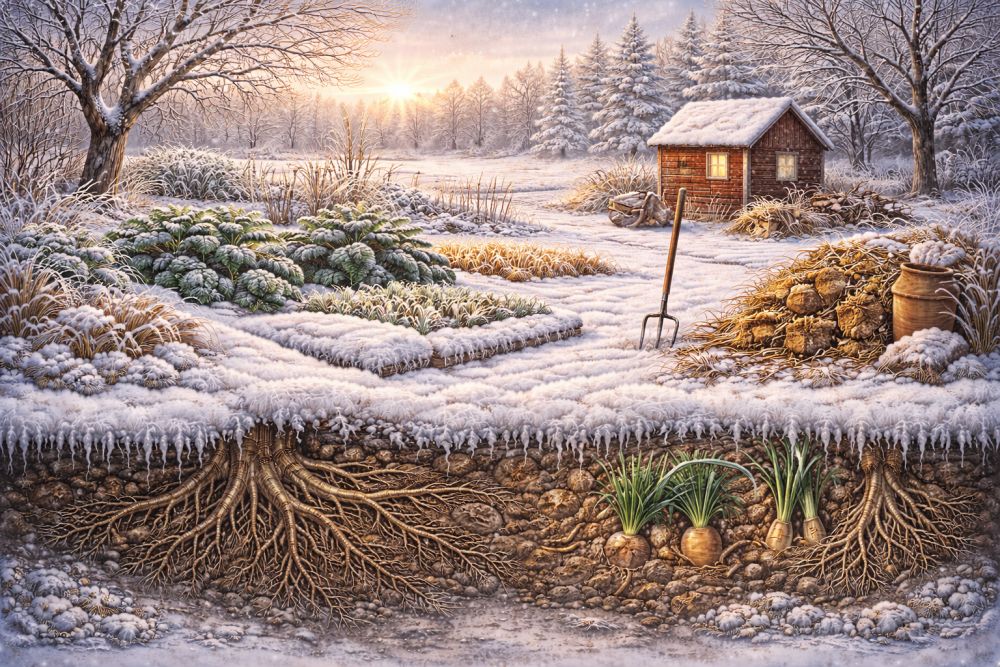

The Day Belonging to Roots, Not Leaves

Across Central Europe and alpine regions, January 20 marked a period when soil was deliberately left undisturbed. Digging, planting, or excessive walking on garden beds was avoided.

The belief was simple but powerful: the earth was alive, just turned inward. Roots were thought to be active in their own way, gathering strength and waiting.

Modern plant science supports this intuition. Even during deep winter dormancy above ground, root systems and soil microorganisms continue low-level activity. Compacted or disturbed soil at this stage can suffer long-term damage.

January 20 therefore became a day of restraint — a reminder that patience itself can be a form of care.

North America: Learning from Plants That Endure

In several Indigenous traditions of North America, midwinter was a time for learning directly from plants that remained visible.

Evergreens, grasses, and hardy shrubs demonstrated different survival strategies. Some conserved water tightly, others bent under snow instead of resisting it. Observation, not action, was the lesson.

January 20 aligned with this mindset: a day to notice which plants endure cold openly, and which survive by retreating below the surface.

East Asia: Standing at the Edge of Great Cold

In East Asian seasonal calendars, January 20 often coincides with or borders Da Han — the Great Cold, the final and coldest solar term of winter.

This period represents the peak of inward energy. From here, the seasonal cycle begins its slow turn toward renewal, even though outward signs may remain unchanged for weeks.

Plants are understood to be preparing internally. Energy is stored, not spent. Roots remain responsive, and future growth is quietly organized.

A Shared Global Understanding

What unites these traditions is a shared respect for stability. January 20 was never about forcing change or anticipating spring too early.

Instead, it taught that:

- steady cold is safer than fluctuating temperatures

- roots deserve protection more than attention

- growth depends on what survives winter, not what rushes through it

These insights echo strongly in modern ecological gardening, where soil health, root integrity, and seasonal timing are central concerns.

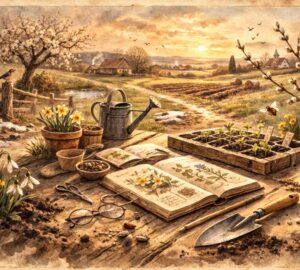

Why January 20 Still Matters

In a world increasingly shaped by erratic winters, January 20 offers a different perspective. It reminds us that stability — even when cold — is a gift.

The garden on this day asks for very little. Do not dig. Do not rush. Do not disturb what cannot yet respond.

Let the cold hold.

That quiet agreement between land and season is what gives January 20 its place in The Garden Almanac.